Alternative Family Structures: the Case for The Girls Next Door

6To my chosen family, with love.

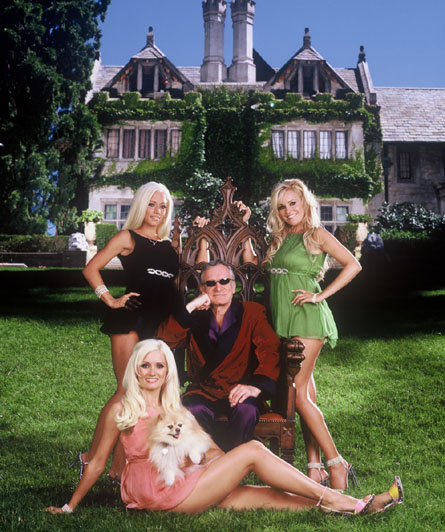

In the spring of 2007, I came upon a happy surprise in my new apartment: free cable television. As a recent law school graduate studying intently for the Colorado bar exam, I took full advantage of this circumstance, and got hooked on a little show called The Girls Next Door. This reality program chronicled the lives of magazine tycoon Hugh Hefner’s three 20-something live-in girlfriends: Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt, and Kendra Wilkinson. The girls lived with Hef in the Playboy Mansion; they dressed up in elaborate (and skimpy) costumes, threw parties, rubbed elbows with Hollywood’s elite, and generally caused mayhem while spending Hef’s money and having an exceptionally good time. Despite the constant presence of television cameras in these women’s lives, they lived with Hef as a family. Holly, Hef’s “Number One Girl,” shared a room with Hef, and seemed truly in love with him; she was never shy about expressing her desire to get married and have children. The other two had their own rooms in the Mansion, but the show always implied they spent intimate time with Hef as well. The group shared meals, spent quiet evenings, traveled, celebrated birthdays and holidays, met each other’s families, fought, made up, and generally interacted like any other family does (well, for the most part). Sadly, in 2009, Holly broke up with Hef and left the Mansion (reportedly because of Hef’s unwillingness to get married and have children). Soon after, Bridget and Kendra followed suit. Hef rebounded as any spry eighty-something man will, and picked up with three more barely-legal women; thus, the show kept going. Of course people make fun of this show; it’s hilarious. But despite the contrived situations and the blatant publicity, I think the original group was a “real” family. And though the structure of that family may have been “alternative,” I think it should have the legal recognition and protections given to more traditional families.

Over the last few years, I have spent a lot of time thinking about alternative family structures; that is, conglomerations of familial interactions and relationships that encompass something different than the nuclear structure. Traditionally, our culture defines “family” as the nuclear family—a structure centered on marriage and including children born out of that marital relationship. This conception of family is imprinted on us from as far back as the beginning of western civilization. In Politics, Aristotle wrote: “If one were to look at the growth of things from their beginning . . . [f]irst, there must be a union of those who cannot exist without each other, that is, a union of male and female. . . .” Aristotle’s Politics, 16-17. Aristotle asserted that nuclear families were the building blocks of society: “We observe that every state is a sort of association . . . . [T]he first association formed from many households . . . is the village, and the most natural form of a village seems to be a colony of household[s] . . . .” Aristotle, 17. This understanding—that the family structure revolving around marriage is essential to the formation of society—is still propagated today. (See Ted Olson, Newsweek, The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage (January 9, 2010), which explains from a family values perspective why our society should support same-sex marriage.)

Not to get too legal on you, but the United States Supreme Court also buys into this view of the family, and prioritizes recognizing and protecting the nuclear structure. C. Quince Hopkins, The Supreme Court’s Family Law Doctrine Revisited, 456-62. Consider the Court’s opinions on the paternity rights of unmarried fathers. For instance, the biological father in Stanley v. Illinois maintained custody of his children, despite not being married to their mother, because they all lived together like a nuclear family for many years before the mother’s death. 405 U.S. 645, 651 (1972). In contrast, the biological father in Lehr v. Robertson did not maintain parental rights of his child because he was neither married to the mother nor involved in the child’s life—his relationship with his child and the child’s mother did not mimic a nuclear family. 463 U.S. 248, 266-67 (1982). Finally, the biological father in Michael H. v. Gerald D. did not maintain visitation with his child because the mother was married to someone else; the Court found preserving the nuclear family emanating from the marital relationship more important than preserving a father-daughter relationship forged outside of that setting. 491 U.S. 110, 120 (1989). These decisions say to me that the nuclear family structure is not just an underlying social force in our culture; it is actively recognized and protected as some sort of higher social good by our highest court. My question is: why? Why are nuclear families important to the exclusion of other family structures?

Despite our covert and overt prioritization of the nuclear structure, there are a lot of families out there that do not fit, or even resemble, that mold. I didn’t seriously consider the existence or viability of “alternative” family structures until my niece was born in 2001, when I started studying the federal Indian Child Welfare Act. That piece of legislation attempts to interject cultural relativism into state child welfare proceedings involving Indian children. That is, it attempts to force state courts in these proceedings to recognize that Indian families do not necessarily conform to the nuclear structure. In its congressional findings, the Act states “that the States, exercising their recognized jurisdiction over Indian child custody proceedings . . . have often failed to recognize the essential tribal relations of Indian people and the cultural and social standards prevailing in Indian communities and families.” 25 U.S.C. § 1901(5). For many Indian tribes, extended family members play a central role in raising Indian children, and parents commonly leave their children with such relatives for long periods of time. B.J. Jones, The Indian Child Welfare Act Handbook, 3 (1995). Because placing a child with extended relatives is a normal part of childrearing in many tribal cultures, the Act sought to eliminate a state’s ability to remove Indian children based on the dominant culture’s presumptions about who and what make up a family; in essence, the Act attempts to recognize and protect Indian families functioning in structures other than nuclear.

Now, keep in mind that Indian families receive very specific federal recognition and protection because tribes are semi-sovereign nations with the ability to self-govern. Yet, these are not the only families outside the traditional that warrant recognition and protection. Indeed, other “alternative” family structures are fighting for legitimacy as I write this. Consider the federal challenge to California’s Proposition 8, currently being litigated in the Northern District of California. The plaintiffs in this trial are fighting for the rights of same-sex couples to get married; to be legally recognized as families and to receive legal protections as such. Though a same-sex marriage is “alternative” in comparison to a heterosexual marriage, it still follows the pattern of a nuclear family (two adults who partake in a legal relationship and who have children pursuant to that relationship if they choose). At the end of the first week of trial, one of the attorneys challenging Proposition 8, Ted Olson, attempted to make the anti-Prop 8 case to conservatives by linking same-sex marriage to the traditional social norms a nuclear family structure promotes and protects. Olson, The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage. Further, judging from Olson’s Newsweek piece and the live courtroom tweets from @ilona and @NCLRights, many of the plaintiffs’ witnesses in this trial have focused on the similarities between long-term heterosexual relationships and long-term same-sex relationships; how these binary relationships promote the traditional values of a nuclear family, and accordingly, societal stability.

Here’s where I get back to The Girls Next Door. I reject the notion that the nuclear family paradigm is the end-all, be-all family structure, the only permutation of a family that can promote societal stability and social good. Federal law requires recognition and protection of non-nuclear Indian families, and legal recognition of same-sex marriage is really just recognition of a nontraditional form of the nuclear family. What about nontraditional, non-nuclear family structures for people outside of special-circumstance groups? I’ve come to the conclusion that if I’m going to respect and fight for some types of alternative family structures, I at least have to openly and honestly consider the value inherent in all types of alternative family structures. After all, just because you personally dislike the way a certain group of people lives, that doesn’t mean it’s objectively problematic and devoid of social value. And we live in the United States; people have constitutional rights regarding whom they associate with. Why shouldn’t different familial structures be recognized and protected in accordance with those rights?

I would submit that Hef and his girlfriends practice what seems to be a socially acceptable form of what our country understands as polygamy. The girls live in the same house, have intimate relationships with Hef, and share him with a seemingly minimal amount of jealousy. There is a head girlfriend, and she has a certain amount of authority over the others. Though there are no children, this is only because the head-of-household is not interested in siring any more. Considering all this, it seems strange that a wealthy octogenarian in Southern California can live in an open relationship with a group of young (sometimes barely eighteen), beautiful women, have the situation put on television, and no one bats an eye; at the same time, similarly-structured families in Utah, Arizona, and Texas have their children removed by child protective services basically for living the same way. See Fox News, Polygamist Parents Complain “Vague” Custody Plans Impossible to Follow (March 20, 2008). If these two groups are the same, then both deserve recognition and protection; both should be legitimized as families.

I realize this thought, that a polygamous family—be it on television in Hollywood or in hiding out on a compound in the Southwest—should have legal recognition and protection, raises concerns about oppression and abuse. Polygamy, in the tradition of the Church of Latter Day Saints, does subjugate women. But the practice of plural marriage itself does not necessarily do so. This is evidenced by the multiple terms utilized to describe different types of plural marriage: according to Wikipedia, “polygamy” is an umbrella term covering both “polygyny” (where a man has more than one wife) and “polyandry” (where a woman has more than one husband). Putting aside our history and gender roles, it is possible for a polygamous family to consist of one wife with multiple husbands. But even inside a polygamous marriage with one husband and multiple wives, the relationship does not have to be one of subjugation, or, at least not any more than any other heterosexual marriage.

Further, regarding underage sex crimes and domestic violence, protections against such behavior within a traditional marriage exist. State laws are beginning to permeate the black box of heterosexual marriage, and presumably these laws can also be used to address problems within a plural marriage. I understand state authorities have difficulty prosecuting sex abuse, child abuse, and domestic violence within polygamous LDS sects, regardless of the laws on the books. This seems to be because these sects have completely closed themselves off from modern society to avoid persecution, and consequently are virtually inaccessible to the outside world, including law enforcement. But if polygamy were legally sanctioned as an acceptable form of family, those doors would probably open up, and state protections against criminal behavior in polygamous relationships could become more effective.

We legitimize Hef and The Girls Next Door by putting them on television. Let’s call them what they are: a family. If we at least socially recognize Hef’s “alternative” family, we need to afford the same recognition to other permutations of this structure. We have criminal codes to take care of the sex abuse and domestic violence alleged in these situations. But as far as I can tell, there is nothing in the constitution prohibiting us from recognizing polygamous family structures along with the other alternative structures we already recognize and protect (or are fighting to recognize and protect).

I know there is some concern about how to draw the line: who counts as family, and who is just trying to scam the system for personal gain? I don’t know how to draw that line; I don’t know which associations “deserve” to be considered family and which do not. Do we really need a line at all? Don’t the personal benefits that any familial relationship brings an individual help that individual contribute positively to our society? Who cares whether my family is mine by blood, legal ties, or my choosing? In actuality, I have all three, and my chosen family is just as pivotal in my life as the biologicals or the legals. I love them with my entire heart; we have followed each other all over the country, we have lived together, we have celebrated birthdays, holidays, and milestones together, we have met each other’s biological families, we have fought, we have made up . . . we consider ourselves as close as any traditional family. My association with them helped me accomplish things I could have never done on my own: finish a thesis, graduate from college, attend law school. They make me a better person, and as a better person, I have more to give back to the world. If a family structure offers an individual these benefits, I don’t see how that structure could not benefit our society; any structure that brings those benefits deserves to be recognized, protected, and promoted.

The Twilight Saga and Surviving Adolescence

7This essay was written in loving memory of Marina Husky Lopez, who did not survive adolescence. We love you and miss you.

Don’t you see, Bella? You already have everything. You have a whole life ahead of you. And you’re going to just throw it away. You have the choice that I didn’t have, and you’re choosing wrong! (Rosalie to Bella) Stephenie Meyer, Eclipse, 166 (2007).

Perhaps some exposition is in order. For those of you living in a cave or under a rock for the last year or so, the Twilight saga is a very titillating, sexually repressed teen romance between a plain, quiet high school girl (Bella) and an attractive, angsty, permanently-teenage vampire (Edward). The story basically chronicles the ups and downs of this relationship, with some vampire/werewolf fighting and a love triangle in between. Bella and Edward’s romance is tumultuous, mostly because Edward experiences a lot of inner turmoil over being in love with a creature that he is designed to hunt and kill. He has a lot of emotional outbursts, which Bella bears the brunt of by proximity. But Bella accepts the roller coaster of their interaction, and decides by the end of the first book that she wants to become immortal (turn into a vampire) so she can be with Edward forever. This—Bella’s willingness to throw away her mortality—I take issue with.

Please note that I’m writing this from the perspective of a fan. I loved these books. I spent an inordinate amount of time parsing through them, rereading my favorite parts, thinking about the minute details, being in love with Edward, justifying Bella’s actions to myself, and generally enjoying them way too much for a thirty-year-old. So these thoughts are expressed out of love. At the same time as I adored these stories, I think it’s important to examine some of their more disturbing aspects. One of those that particularly struck me is the trajectory of Bella’s goals and life. Bella’s main goal is to be with Edward; so much so that she’s willing to give up her mortality for it. As a result of her decision to trade her mortality for her man, I don’t think Bella survives adolescence; I think she dies. And I find that incredibly disturbing, especially in light of the fact that millions of teenage girls (not just thirty-something women) have eaten this story up. Surviving adolescence is something many teenage girls do not think they will do. We’ve all been there; it’s such a trying time in life, and most of us wouldn’t relive it for all the money in the world. But somehow we make it through; that one B- didn’t end our careers, that gossip about us didn’t end our social lives, breaking up with our first love when it just didn’t work anymore didn’t end the universe. Some of us had deeper struggles, and coming out of adolescence alive and in tact was an enormous accomplishment. Therefore, I find Bella’s willingness to give up life based on the flush of emotion that accompanies first love insulting; it’s kind of a slap in the face to those of us who have worked so hard to pull through childhood and live as strong and independent adults, fighting to be good role models for our sisters, nieces, and daughters. I’m scared to think about what kind of effect Bella’s decision has on younger readers.

I know, I know, Bella becomes a vampire; she doesn’t die. But what does it really mean to become a vampire? When Bella is finally changed, she gives this first-hand account:

My heart took off, beating like helicopter blades, the sound almost a single sustained note; it felt like it would grind through my ribs. The fire flared up in the center of my chest, sucking the last remnants of the flames from the rest of my body to fuel the most scorching blaze yet. . . . [M]y heart galloped toward its last beat. The fire constricted, concentrating inside that one remaining human organ with a final, unbearable surge. The surge was answered by a deep, hollow-sounding thud. My heart stuttered twice, and then thudded quietly again just once more. There was no sound. No breathing. Not even mine. Stephenie Meyer, Breaking Dawn, 385 (2008).

In Meyer’s mythology, becoming a vampire is very painful; your heart stops beating, your lungs stop breathing. Blood no longer flows through your veins, accounting for your pale countenance. You don’t eat (in the traditional sense), you don’t sleep, and you don’t change. You keep the same characteristics and attributes you had at the point of transformation; you don’t develop, grow, or mature, either physically or emotionally. All of these factors indicate to me that becoming a vampire is dying. You are no longer mortal; you are no longer human; your being no longer interacts with time. Some might argue that this transformation isn’t death; it’s just that the parameters of existence have changed for a person who goes from human to vampire. But don’t the parameters of existence also change for a person who goes from life to death? And what is death, if not the obliteration of one’s humanity and mortality, and, as far as those of us left alive know, the stopping of the clock, freezing one in time? Other characters in this saga appear to agree with me. Rosalie likens the transformation to death on multiple occasions. In the Cullen family vote regarding whether Bella should transform, she votes for Bella to maintain mortality, saying she wished someone had chosen differently for her. Later, she divulges her tragic story of transformation and chastises Bella for choosing to throw life away. Edward, the most skittish Cullen regarding changing Bella, definitely thinks the transformation constitutes some type of death; he doesn’t want Bella to make the change because he’s afraid it will claim her soul. He fights for her humanity and mortality throughout the series, trying to assuage her decision by first leaving her, then blackmailing her with college and marriage, and finally enticing her with sex.

If vampirism is death, why does Bella choose it? Of course, the easy answer to this question is she chooses it to keep her man. Which is not exactly a healthy or admirable goal for an eighteen-year-old. I know, I know, this story is a fantasy; it not only involves mythical creatures, but it’s about what we would do if we could do (hold on to that first “true love”), not what we actually have to do (let it go and move on). But think about it. If vampirism is death, not only does Bella not live through her adventures, she doesn’t even want to. She wants to die. She wants to permanently preserve the state of emotion that is falling in love for the first time. Rather than sucking it up and surviving a notoriously difficult time in life, Bella cops out and chooses permanent adolescence. And my resulting question is: how can she be a reasonable heroine if she doesn’t make it through?

I find Bella’s goal of vampirism throughout this saga particularly perplexing because I don’t think she is necessarily a weak character; I can’t just write her off as a ditzy girl without empathy or intellectual capabilities, a person who needs to be taken care of. Bella is a very conscientious young woman with a high capacity for the strange and unusual. She puts a lot of thought and energy into the feelings and comfort of her loved ones. She loves people/creatures unconditionally, regardless of who they are, and sometimes regardless of how they treat her. She wants to protect them, to fight for them and with them, and she hates that she doesn’t have the physical strength to run with monsters. She doesn’t like sitting safely in the back while others risk their lives on her behalf. She wants to do her part.

Bella is also emotionally sophisticated; she is a very serious young woman who thinks a lot about her emotional existence, prioritizing it over her physical existence. She’s in tune with her emotional self, and she feels what she wants with the full force of her emotions. However, despite her emotional sophistication, she is incredibly emotionally immature. This makes sense; she is only eighteen, after all. This immaturity is shown by the fact that she has no sense of physical self-preservation, only emotional self-preservation. When it comes to becoming a vampire, Bella doesn’t care about the risk to her physical body. She also does not consider the effect her transformation will have on her physical environment: she doesn’t ever really face what her changing will do to her mortal family and friends, or the impact it will have on those relationships. (And this is a point Meyer never really works out satisfactorily; for instance, Bella maintains a relationship with her father after her transformation, but not with her mother, to whom she is supposedly closer.) Bella’s only focus is the longevity of the one relationship, and how maintaining that relationship at any cost will help her avoid experiencing the emotional pain that comes with separation from Edward. Her youth and inexperience fuel her obsession with her man. That love/obsession causes her to give up her mortality. Her decision to change denies her the opportunity to turn her emotional sophistication into emotional maturity. All the potential to grow into a mature, independent woman is there, if only she could see beyond the cloud of emotions she seeks to infinitely preserve.

Experiencing, and living through, emotional pain (particularly the pain of first love) is part of the process of becoming an adult. Bella’s rejection of that process says to me that she doesn’t want to mature; she doesn’t want to grow up. (The saga is fairly explicit regarding Bella’s aversion to physically aging; however, I think the fact that she also displays an aversion to emotionally maturing is less noticeable and more troubling.) Is Bella’s ability to make her dream-like adolescence permanent why so many thirty-something women relate to her? (Indeed, I have seen some well-educated women, myself included, go nuts over these stories.) Is it because Bella is able to preserve the things we wanted so badly when we were eighteen; because she takes a route we weren’t able to take? That makes sense to me. I don’t have a female friend who wouldn’t want to relive those first love feelings (though perhaps not the entire first love experience). Some of us still look for that now, and against our better judgment, make long-term relationship decisions based on that rush of emotions rather than considering the realities of living with another person for an extended period of time. Bella’s fantasy is fine for (most of) us; we’ve at least seen these adolescent experiences to completion, know the sky doesn’t fall when that love is over, and are capable of handling new loves that come along with a more mature eye. But what about the readers who are still in the throws of adolescence? What message does it send to them? “Don’t be concerned with surviving the emotionality you are experiencing”; “don’t try to live through it and learn from it”; “this emotion can/will last forever, and you should do what you can to make it”? At the very least, having Bella as a major cultural figure/role model can’t be helping teenage girls see the temporary nature of what they are going through. I definitely don’t think these are productive messages for young girls, regardless of your political/religious/moral bent.

To be fair, Bella is slightly redeemed by the time she changes; after all, she does choose life, for a short period. After her wedding, after discovering how good sex can be, she decides she’ll live a few more years as a mortal, maybe go to college, and have sex with her husband every night. These happy plans end quickly; Bella finds out she is pregnant on her honeymoon. Because the baby is half vampire, with many vampire attributes and growing at a rapid rate, Bella is not expected to survive the pregnancy. Therefore, in order for her to exist in the world and be a mother to the child, Bella must become a vampire. Yet, it’s a waiting game. She can’t be changed too early, or her transformation will kill the baby. But if the Cullens wait too long to change her, it will be too late; she’ll be killed by a half-vampire creature ripping through her during childbirth. In creating this conflict and taking Bella to the brink of death before changing her, Meyer offers some redemption for Bella’s previous easy willingness to give up her mortality. Yet, Bella’s transformation under these circumstances is almost too neat of a package. It’s admirable (?) of Meyer to try to make Bella’s sacrifice of her mortality necessary, but this situation comes at the tail end of a ~3000-page saga, throughout most of which the heroine is begging to give up her life to be with her boyfriend. I don’t know if it’s enough. I don’t know if it’s enough to redeem Bella’s previous attitude, and I don’t know if it’s enough to convince us that Bella would have stuck to her post-sex decision to choose mortality had she not gotten pregnant.

Personally, I find a lot of beauty in a finite life, a human life that hopefully has the opportunity to run a normal course through time. To willingly cut off your mortality before you’ve even begun . . . I have a hard time getting behind that, even in a fantasy world where teenage girls fall in love with vampires and werewolves. Despite the fantasy, the underlying message doesn’t go away. Any way you slice it, Bella still loses her human life, and that’s the way she wants it. She does it to infinitely preserve her adolescence; she does it to avoid growing up. And I think that is a tragedy; for her potential as a character, for the millions of girls who have read about her and want to be like her, and for the legacy of the millions of women who have worked so hard to move beyond all that.

MJ: What do his life and death say about us?

1We can’t pity him. That he embraced his destiny, knowing how fame would warp him, is what frees us to revere him. . . .

“Deep inside I feel that this world we live in is really a big, huge, monumental symphonic orchestra. I believe that in its primordial form, all of creation is sound and that it’s not just random sound, that it’s music.”

May they have been his last thoughts. John Jeremiah Sullivan, Back in the Day, GQ Sept. 2009.

This past July, a lot of bloggers expressed irritation about how much media coverage Michael Jackson’s June 25 death received, especially in comparison to Walter Cronkite, who died a few weeks later. To them I say, sure, I agree that MJ was probably not as culturally significant as Cronkite, at the very least by virtue of the fact that Cronkite lived 42 years longer than Jackson. Neither is MJ’s death as politically important as our economy, our war with Iraq, our escalating problems with Iran and North Korea, our upcoming surge in Afghanistan, or our healthcare reform (to name a few national concerns). On the other hand, MJ’s life is a compelling story because it is so very difficult to reconcile his gifts with his foibles. His story is a cautionary tale; the ways in which a small child can be ruined by others, the ways in which an adult can ruin himself. Despite all he accomplished, MJ was a pretty damaged person; partially through circumstance, and partially through his own making. People are trying to figure out what his life meant, to him, his family, the entertainment industry, his fans, and the world at large. Thinking about MJ’s life is a lot harder than thinking about Cronkite’s life. Cronkite doesn’t have a narrative that splits in two in the middle. He had a fairly singular trajectory. MJ rose to heights we can only imagine through his work, and fell to depths no one wants to experience through his personal travails. What does that mean to us? What does that mean to those of us who display similar mental health issues, but lack similar talent? Are we relegated to an existence similar to MJ’s worst times? Or are those situations reserved for the very mentally ill who also happen to be the very wealthy? If so, what does MJ’s life say about celebrity- and fame-culture in the US? What does it say about wealth and excess? Fame and wealth are things everyone wants a little piece of; I don’t care who you are, you’ve thought about what it would be like to be a rich and famous celebrity. Otherwise, why would reality television be so successful? Why would people like Heidi Montag, Lauren Conrad, Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian, etc. be trying so desperately to claw their way to the top of the entertainment tower without having any entertainment skills to speak of? And what does MJ’s life say about other child stars who have fallen apart much younger and much faster? The slow-burning self-destruction of Michael Jackson has been played out in double-time for Britney, Lindsay, and a host of others. They seem to have one thing in common with MJ; not necessarily his talent, but instead similarly pushy, money-hungry, stage parents trying to live out their own dreams through their children (and hanger-on siblings trying to leverage themselves off the former’s successes). MJ is a lesson in what constitutes very poor parenting, to say the least.

These aren’t insignificant or trivial questions, and some of them verge on existential. They are not easily answered, and they are why American society is having its own meltdown—played out via excessive media coverage—over losing Michael. They make us—at least MJ’s fans, if not American society as a whole—consider this person’s existence in more than black and white (no pun intended; sorry MJ). The story of Michael Jackson, the trajectory of Michael Jackson, cannot fit in a box. He doesn’t make sense in terms of an overarching narrative. That’s because his existence, like everyone else’s existence, is much more nuanced than that. His otherworldly highs, combined with his dramatic lows, create a very stark example of how a person’s worth can’t really be painted in such broad strokes. We can’t effectively judge whether this person was good or bad (though I’d point out the basic: no one is pristinely good, or completely evil), and we’re not used to having our narratives limited by nuance like that. We’ve relegated MJ to the obscure, the bizarre, and even the criminal for many years now, but he was extremely prominent in the public consciousness for quite a while, and his successes can’t be ignored any more than his questionable judgment and suspect behavior. How do we, a society that has historically focused on quick answers and simple narratives to explain ourselves, make sense of Michael Jackson? Time and revisionist history have allowed us to forget a lot of our dichotomous past, but with MJ, the ups and downs of his existence all happened in the span of a very short 50 years. Combine that short time with modern media accessibility, and you end up with a public processing problem. Nothing about MJ can be swept under the rug, and nothing can be ignored. It’s all out there for us to consume, examine, and ruminate on. We’re almost forced to do so. And it’s stark and scary. It’s scary to think someone who reached orbit professionally could fall so far personally, and it’s scary to try to reconcile that.

As MJ’s death forces us to examine the nuances of his life, his life makes us examine our pervasive, sometimes subconscious, societal goals of fame and wealth. The results, and their broader implications, are also unnerving. MJ’s life shows that happiness does not automatically accompany success as measured by fame and wealth. Many people understand this concept intellectually, and other public figures’ lives also show it, I suppose. But MJ’s story proves it in a very drastic way. And our confusion over MJ’s dichotomous life goes to show that no matter what we know intellectually, societal currents are strong; we still expect a person with MJ’s success to be happy as a result; it’s a permutation of the American dream. The fact that he wasn’t seems almost unreasonable. But the man was probably never truly happy at any point, not even during the height of his career (he was reportedly so lonely during the Off the Wall/Thriller years that he couldn’t even contemplate moving out of his parents’ house, at the age of 23-24). His life very loudly declares that being the best doesn’t necessarily make a person happy; being the richest doesn’t necessarily make a person happy; being the most famous doesn’t necessarily make a person happy. So if the factors our culture understands as happiness-making do not actually accomplish happiness, then what goals should our society advocate for us to pursue in order to reach that equilibrium in our time on earth? Does religion really provide the answer? (After all, plenty of religious people still feel compelled to pursue fame and fortune.) Does art? Obviously neither art nor religion helped MJ, despite his strong roots in both. What should our societal goals for life be, if not pursuing these measures of success, which function as calibrations of happiness? If we know, intellectually, that these values do not actually make our lives better once realized, should we be taking a more active role in rooting them out of our collective consciousness and replacing them with more psychologically healthy and socially beneficial values? What kind of social movement would that type of change necessitate? Is that kind of change even possible? What does it say about us if we try, and what does it say about us if we don’t?

Ultimately, I didn’t mind the MJ coverage; his story took up an incredible amount of space in my head and every little piece of information seemed to help me gain a clearer picture of the man, and consequently the meaning of his life, for my own resolution as a fan. But as to those who were and are bothered, I really think this man’s life and death could and should stimulate a societal self-examination/self-reflection that we need. The important points bear repeating: how do we reconcile such disparate narratives in one person? We need to learn; it’s hard to see how we can keep painting our world in broad strokes and simultaneously expect to have any sort of accurate view of it, especially in the age of extremely accessible media. And what do our values mean if a person who exceeded every one of those hopes and dreams still had a monumental meltdown? It’s hard to see how those should remain our values, to say the least. I don’t know what the answers are, but I think the questions are worth thinking critically about. In death, as he saw himself in life, MJ is just a vessel. In life he saw himself as a vessel for music, dance, and art; in death he is a vessel for a reexamination of the quintessential American success story. He is necessary to us in that way. I guess I hope we not only learn the lessons, but also work to “make that change.” I don’t know how to make any more sense of his story, and our obsession with it, than that.

Indian Killer and the Indian Child Welfare Act

0“Please,” John whispered. “Let me, let us have our own pain.” John . . . quickly walked to the edge of the building, and looked down at the streets far below. He was not afraid of falling. John stepped off the last skyscraper in Seattle. . . . It was quiet at first. . . . He listened to the silence, felt a heavy pressure in his spine, and opened his eyes. . . . John looked down at himself and saw he was naked. Brown skin. . . . An Indian father was out there beyond the horizon. And maybe an Indian mother . . . . John wanted to find them both. He took one step, another, and then he was gone. Sherman Alexie, Indian Killer, 411-13 (1996).

In his novel Indian Killer, Sherman Alexie provides a vivid description and account of John Smith, a twenty-seven year old American Indian raised by his adoptive white parents in Seattle, Washington. Id. John’s life and problems make him the perfect embodiment of the harm to Indian children that Congress attempted to prevent by passing the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978. 25 U.S.C. § 1901 (pdf). He is an Indian child, removed from his mother at birth without apparent cause, and adopted by a white family. He gains a white identity in his youth, only to find that it is not really his own as a teenager, when he starts to face discrimination and abuse. But he does not have an Indian identity either; he is not even aware of the tribe he comes from and his only exposure to Indian culture is a conglomeration of generalized, stereotyped intertribal information that his parents so diligently try to provide him with. In this identity abyss, John first becomes angry, and then he becomes mentally ill. Finally, after a flurried night of pain and confusion, John ends his own life. John’s life is the anecdote that is cited in the legislative history of the ICWA, and is often cited as the main purpose behind the Act. In utilizing this generalized, anecdotal experience of the American Indian child removed from his or her Indian home, Alexie ends up creating an incredibly moving account of the pain and heartache actually caused. Alexie’s story about John puts life into the legislative anecdote and perhaps indicates that the anecdote may actually be as broad-based as it claims. At the very least, John’s story allows the non-Indian a chance to see a realization of the Act’s generalized Indian child, which could serve to garner much-needed sympathy and support for the ICWA.

In 1978, Congress passed the ICWA. Its stated declaration of policy is “to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by the establishment of minimum Federal standards for the removal of Indian children from their families and the placement of such children in foster or adoptive homes which will reflect the unique values of Indian culture . . . .” § 1902. The ICWA was passed because Indian children were being removed from their homes in record numbers; 25-35% of all Indian children were living in foster and adoptive placements at the time the Act was passed, and 85% of those Indian children were residing with non-Indian families. H.R. REP. NO. 95-1386, at 9 (1978) (pdf). The generalized story of an Indian child removed from his or her Indian home that underlies the Act has four main elements. First, the child is generally removed from his or her Indian home by a state child welfare worker who is not privy to tribal social practices. Id. at 9-10. The worker most often removes a child based on the dominant culture’s theory of parental abandonment, because the child has been residing with an extended relative (rather than the parent) for a prolonged period of time. Id. at 10. The Indian child is then placed in a white foster or adoptive home, and after such placement retains no connection to his or her Indian family or tribe. Id. at 9. The child maintains a white identity until discovering he or she is not actually white. This usually happens as a teenager, when outsiders treat the child differently. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30, 33 n.1 (1989). Finally, with all of this identity confusion the child grows into a very confused young adult and tends to display “maladaptive behaviors” such as mental health problems and drug abuse. B.J. Jones, The ICWA Handbook 4 (1995). The suicide rate among young adult Indians remains very high.

Alexie’s portrait of John Smith meets all four of these elements. First, John was removed from his Indian home at birth. Born in 1968, John’s adoption occurred ten years before the ICWA was enacted. It is not entirely clear what the circumstances of his adoption were. As John envisions it, his mother was a fourteen year old Indian woman living on a reservation. She gave birth to him in an IHS hospital, and he was immediately torn from her arms and taken by helicopter to his white adoptive parents. Alexie at 3-8. Regardless of the accuracy of this vision, John was definitely taken from his mother under questionable circumstances. Daniel and Olivia Smith, John’s white adoptive parents, are talked into adopting an Indian baby by the adoption agency because Indian babies are “less popular” than white babies. Id. at 9. The adoption agency official is quick to correct this language, but goes on to lump babies of color with physically handicapped and mentally retarded babies. The agent tells Daniel and Olivia that there is not an Indian home available for the Indian baby, but then goes on to say: “The best place for this baby is with a white family. The child will be saved a lot of pain by growing up in a white family. It’s the best thing, really.” Id. at 10. The fact that the adoption agency tells Daniel and Olivia that an Indian baby is much more readily available than a white baby, coupled with the agent’s attitude concerning what type of placement is in the baby’s best interest, supports the conclusion that John was removed from his mother without reason; something the ICWA was enacted to guard against. Even if John’s mother reportedly “chose” to give the child up for adoption, the agent’s attitude indicates possible coercion. Otherwise, it does not make sense for the agent to feel the need to reassure the Smiths that the mother is doing the right thing, or that placement in a white home is actually in the child’s best interest. Id. Additionally, removing John from his teenage mother implicates the dominant culture’s notions of parental fitness. Whether the mother would have been considered fit on the reservation and in her tribal community is never addressed, but the fact that she is so young speaks to the non-Indian’s understanding of age-appropriate behavior. The agent’s comment about the mother’s choice being the “right” choice also goes to the mother’s perceived ability to care for her child based on non-Indian parenting standards; another factor that the ICWA was enacted to guard against.

Second, John was placed in a white adoptive home, and retained no connection to his Indian relatives or tribe. Daniel and Olivia knew being a white couple with a brown child was not going to be easy, and did their best to give John a sense of his Indian self. However, the adoption agency would not give the Smiths John’s tribal affiliation or any information about his birth family, other than the fact that his mother had been fourteen when she gave birth to him. Id. at 12. So Daniel and Olivia did their best to give John a general sense of what it meant to be Indian. Olivia scoured books on Native Americans, looking for any child that resembled her child in an attempt to decipher John’s tribe. Id. at 12. She read history books about widely-known tribes and famous Indians from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Id. She bought children’s books about Indians and read them all to John. Id. She learned basic words in several different Indian languages, and tried to teach them to John. Id. She watched westerns and documentaries, and stopped Native people in the grocery store to ask them questions about being Indian. Id. Olivia and Daniel even had John baptized Catholic by a Spokane Indian priest named Father Duncan, who served as John’s only real Indian connection until he was an adult. Id. at 13. His parents also took him to Indian events, such as powwows and Indian basketball tournaments. Id. at 20. But after all of this well-meaning effort on the part of two non-Indian parents, John still ended up in an identity crisis. His knowledge of Indian identity was an intertribal conglomeration of myths and words and historical figures, not the identity of an actual Indian. And when he was in an all-Indian crowd for the first time, at the Indian basketball tournament, he just felt betrayed by what his parents tried to teach him because the Indians there were nothing like what he had imagined Indians to be. Id. at 22. John’s continued fear and sadness into adulthood despite his parents’ best efforts at first, raising him in a loving, supporting, upper middle class family; and second, giving him a taste of Indian background and culture, supports the idea that Indian children are seriously harmed when denied the ability to connect with their Indian families and heritages. John’s ultimate disposition also supports the conclusion that a generalized, stereotypical overview of “Indianness” is not enough “connection” to really benefit an Indian child placed in a white home.

Third, John realized he was different from his parents at a very young age, but the difference really seemed to hit home when he was a teenager. John first realized that he was not the same as his parents when he was five years old. Id. at 305. He walks into his parents’ bedroom without knocking and finds them in their underwear. Id. Taking note of their pale skin, John runs out of the room and outside to his favorite tree. Id. at 306. There he ponders the difference between his color and the color of his parents (“translucent” for Daniel; “milk” for Olivia) and attempts to wipe the brown off of his face so that he will look like them. Id. But this incident is not to say that he did not have a dramatic realization about himself as a teenager. He was only one of four boys of color at St. Francis Catholic High School, and he was the only Indian. Id. at 19. Dating white girls in high school brought his difference into sharp relief and caused him almost uncontrollable anger. Id. at 17-19. The girls’ fathers started out uncomfortable with him, and their irritation grew as he continued to go out with their daughters. Id. at 17. The girls inevitably broke up with him, and in his mind it was a product of their fathers’ discomfort. Id. at 18. Any given father would have a problem with his dark skin; assume he was an indigent scholarship student; or attribute to John a host of issues based on his adoption status. Id. Though the girls never mentioned their fathers when breaking up with John, this sort of attitude on the part of non-Indian parents has historical support. As noted by a psychiatrist who testified to the negative effects of non-Indian adoption of Indian children in the ICWA hearings of 1974:

[Indian children] were raised with a white cultural and social identity. The are raised in a white home. They attended, predominantly white schools, and in almost all cases, attended a church that was predominantly white, and really came to understand very little about Indian culture, Indian behavior, and had virtually no viable Indian identity. They can recall such things as seeing cowboys and Indians on TV and feeling that Indians were a historical figure but were not a viable contemporary social group. Then during adolescence, they found that society was not to grant them the white identity that they had. They began to find this out in a number of ways. For example, a universal experience was that when they began to date white children, the parents of the white youngsters were against this, and there were pressures among white children from parents not to date these Indian children . . . . [T]hey were finding that society was putting on them an identity which they didn’t possess and taking from them an identity they did possess. Holyfield, 490 U.S. at 33 n.1.

John’s personal experiences up to high school mirror this testimony. John was raised in a white home with white adoptive parents; attended St. Francis, a predominantly white school; attended the Catholic Church, which in Seattle is predominantly white; and came to understand Indian culture only through the scattered information his parents could provide and the Spokane Indian Catholic priest. Though realizing at a young age that he did not have white skin, it was in high school that John realized his non-white skin relegated him to a status of less than a real person. Alexie at 19. This realization came through the experience of dating several white girls whose white fathers did not approve of the coupling. It was in high school that John started displaying serious mental health problems, and it was in high school that John realized he had no identity.

Fourth, John’s identity void first causes extreme anger, then severe mental health problems, and finally his death by his own hand. John begins to experience nearly uncontrollable anger in high school, and puts considerable effort into pushing it down and holding it in. In the middle of class he would have to get up and go to the bathroom. Id. He would lock himself in a stall and fight his anger by biting his tongue and lips until they bled, holding himself tightly until he shook, shutting his eyes and grinding his teeth. Id. The intensity of his anger increased such that by the time he was a senior he was taking these side trips to the bathroom on a daily basis. Id.

As an adult, John’s anger turned into something much deeper and more sinister. Alexie does not specify exactly what is wrong with John, but his actions indicate a serious mental health disorder, such as schizophrenia. John experiences visual and audio hallucinations, he is unable to socialize with people (white and Indian alike), he does not like to be touched, he is paranoid about being poisoned, he does not speak logically, he has violent fantasies and tendencies, and he is very unpredictable. For example, John’s visual hallucinations often include Father Duncan walking in the desert; and he is constantly questioning if what he sees is actually real. See id. at 269. His audio hallucinations consist of voices in his head pulling him in opposite directions, and sometimes just plain screaming.

As for socializing, John struggles to interact with his parents, mostly telling them to go away and leave him alone when they come to his apartment to visit him. But he does not socialize well with non-whites either. He struggles to communicate with Marie Polatkin, the Spokane Indian woman he meets at a powwow at the University of Washington. And he has a difficult time communicating with Paul and Paul Too, the graveyard shift counter clerk and security guard, respectively, at Seattle’s Best Donuts. These men he sees and speaks with on a very regular basis, but remains jumpy and paranoid around them. Id. at 99-100. John even has a difficult time talking with the homeless Indians under the bridge; they are constantly asking him what his tribe is, and he always feels uncomfortable at that question because he does not know. John also has a difficult time with physical interactions. He does not like loud noises, and he does not like to be touched. And he is continually paranoid that someone has poisoned him. Though he goes to Seattle’s Best Donuts often, he still has Paul Too, the security guard, take a bite of his donut and a sip of his coffee before he will have any himself. Id.

John’s mental illness also manifests itself in violent tendencies. Soon after John’s story begins, we find him fantasizing about killing a white man, and entertaining a vision of his foreman falling off one of Seattle’s skyscrapers. Id. at 24-25. At one point he even tells a priest that he has killed two white men, though Alexie indicates that this is actually not the case. These fantasies turn close-to-real when he very nearly beats the hell out of Jack Wilson with a sawed-off golf club one evening. Id. at 268-69. Yet he is not consistently violent. He lets Reggie Polatkin beat on him at Big Heart’s Soda and Juice Bar, and he takes some roughing up from Aaron Rogers under the viaduct before Marie comes to the rescue. Id. at 373-75. The inconsistencies in John’s behavior seem to be further proof of his mental illness. Sometimes he has violent rages, and sometimes he can hardly hold himself up.

Finally, John ends his life (though not until after kidnapping Jack Wilson and giving him a nasty cut along the face). Id. at 411-13. John takes the last remnants of his rage out on Wilson—a faux Indian—by asking him to “[l]et me, let us have our pain,” essentially asking Wilson to take the white identity he has and leave the Indian identity for the Indians who have been deprived of their own. Id. at 411. Then John steps off the building, Seattle’s last skyscraper. Id. at 12. Alexie leaves us to imagine that the first time John is truly at peace with himself and his Indian identity is at the point of death, when his spirit looks down, takes note of his brown skin, and steps away from his body to finally start his search for Father Duncan and his Indian mother. Id. at 413. John’s life makes the tragic but frequent tale of American Indian children removed from their Indian homes and placed with non-Indians come to life.

All of these experiences (except for the suicide) parallel the experience of an Indian boy documented by psychiatrists attempting to insert cultural factors into the DSM-IV diagnostic system. Douglas K. Novins, A Critical Demonstration With American Indian Children 1244 (1997). The child is documented at intervals from age eight, when he was removed from his Indian mother and placed with a non-Indian family, to age sixteen, when he was reunited with his Indian mother. During the time he was with his non-Indian foster family, this child displayed aggressive outburst and oppositional behavior, along with a tenuous Indian identity (identifying himself as “half-Indian”). Id. at 1247. By the time the boy is sixteen he is returned to his mother and displays a strong Indian identity, along with slightly better behavior. However, in the interim he began abusing drugs and alcohol, and played Russian roulette with a friend who did not make it through the game. Id. This example shows that John’s mental health experiences and “maladaptive behavior” very closely mirror that of other Indian children removed from their Indian homes and placed with non-Indians. The psychological study indicates that Alexie is not exaggerating, and the problems inflicted on these children are very real.

The narrative Alexie provides of John Smith, though incredibly sad, may actually do productive work in the legal system. It is often difficult for politically liberal non-Indians to understand the value of the ICWA and how it helps Indian children, families, and ultimately tribes. Politically liberal non-Indians tend to believe in nurture over nature, as well as maintaining vigilance about providing constitutional guarantees to everyone in the United States. What these activists do not realize is that first, even though an Indian child is raised in a white home, the racial sentiments buried in our culture still keep the child out of his or her acquired white identity. Thus the Indian child raised in a white home is left with no identity. Second, Indian tribes are semi-sovereign nations with their own governmental structures and constitutions. Tribes’ sovereign status leaves them in a position to take or leave the United States Constitution on their own land, and the ICWA’s jurisdictional provisions aim to protect this sovereignty. The story of John Smith brings home the first point: Indian children need to remain connected to their tribes. John’s life is a graphic illustration of the damage separation from the tribe can do to an Indian child. The ICWA was passed to help facilitate and protect this connection, and does so by granting tribes exclusive and concurrent jurisdiction over Indian children.

Some state courts, especially in California, have been questioning the constitutionality of the ICWA based on substantive due process and equal protection. These courts have decided that if there is no “existing Indian family” from which the child came from, then the ICWA violates both the substantive due process right of children to have permanent placement and the equal protection right of Indian children to not be disparately treated based on genetic heritage. See Bridget R., 41 Cal. App. 4th 1483 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996) (pdf). Some courts have found that when a child lacks any connection with his or her tribe, such as when he or she is removed from the Indian family at birth, then there is no “existing Indian family” and the ICWA is unconstitutional as applied. See Alexandria Y., 45 Cal. App. 4th 1483 (Cal. Ct. App. 1996). But John’s story shows us that an Indian child need not be ripped from an “existing Indian family” in order to be harmed by placement with a white family. Indeed, John lived an upper middle class life with the Smiths, and was never lacking in either material needs or love and support on the part of his parents. Yet he still fell apart. As one commentator put it:

I think the cruelest trick that the white man has ever done to Indian children is to take them into adoption courts, erase all of their records and send them off to some nebulous family that has a value system that is A-1 in the State of Nebraska and that child reaches 16 or 17, he is a little brown child residing in a white community and he . . . has absolutely no idea who his relatives are, and they effectively make him a non-person and I think . . . they destroy him. Holyfield, 490 U.S. at 50 n.24.

Perhaps by giving life and a voice to the general trauma story experienced by Indian children, Alexie’s narrative can help expose non-Indians to the very real harms experienced by Indian children such that state courts will rethink the rationality and legality of this particular judicially-created exception.