Mixed Bag

Alternative Family Structures: the Case for The Girls Next Door

6To my chosen family, with love.

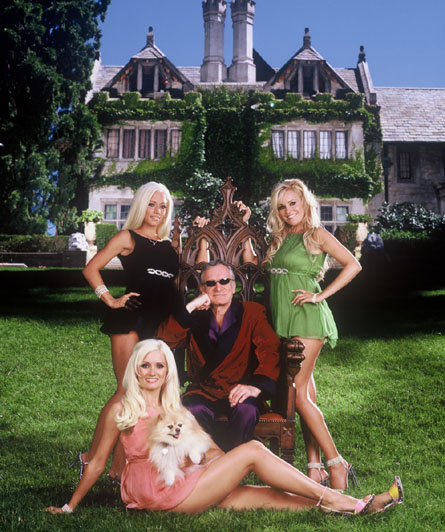

In the spring of 2007, I came upon a happy surprise in my new apartment: free cable television. As a recent law school graduate studying intently for the Colorado bar exam, I took full advantage of this circumstance, and got hooked on a little show called The Girls Next Door. This reality program chronicled the lives of magazine tycoon Hugh Hefner’s three 20-something live-in girlfriends: Holly Madison, Bridget Marquardt, and Kendra Wilkinson. The girls lived with Hef in the Playboy Mansion; they dressed up in elaborate (and skimpy) costumes, threw parties, rubbed elbows with Hollywood’s elite, and generally caused mayhem while spending Hef’s money and having an exceptionally good time. Despite the constant presence of television cameras in these women’s lives, they lived with Hef as a family. Holly, Hef’s “Number One Girl,” shared a room with Hef, and seemed truly in love with him; she was never shy about expressing her desire to get married and have children. The other two had their own rooms in the Mansion, but the show always implied they spent intimate time with Hef as well. The group shared meals, spent quiet evenings, traveled, celebrated birthdays and holidays, met each other’s families, fought, made up, and generally interacted like any other family does (well, for the most part). Sadly, in 2009, Holly broke up with Hef and left the Mansion (reportedly because of Hef’s unwillingness to get married and have children). Soon after, Bridget and Kendra followed suit. Hef rebounded as any spry eighty-something man will, and picked up with three more barely-legal women; thus, the show kept going. Of course people make fun of this show; it’s hilarious. But despite the contrived situations and the blatant publicity, I think the original group was a “real” family. And though the structure of that family may have been “alternative,” I think it should have the legal recognition and protections given to more traditional families.

Over the last few years, I have spent a lot of time thinking about alternative family structures; that is, conglomerations of familial interactions and relationships that encompass something different than the nuclear structure. Traditionally, our culture defines “family” as the nuclear family—a structure centered on marriage and including children born out of that marital relationship. This conception of family is imprinted on us from as far back as the beginning of western civilization. In Politics, Aristotle wrote: “If one were to look at the growth of things from their beginning . . . [f]irst, there must be a union of those who cannot exist without each other, that is, a union of male and female. . . .” Aristotle’s Politics, 16-17. Aristotle asserted that nuclear families were the building blocks of society: “We observe that every state is a sort of association . . . . [T]he first association formed from many households . . . is the village, and the most natural form of a village seems to be a colony of household[s] . . . .” Aristotle, 17. This understanding—that the family structure revolving around marriage is essential to the formation of society—is still propagated today. (See Ted Olson, Newsweek, The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage (January 9, 2010), which explains from a family values perspective why our society should support same-sex marriage.)

Not to get too legal on you, but the United States Supreme Court also buys into this view of the family, and prioritizes recognizing and protecting the nuclear structure. C. Quince Hopkins, The Supreme Court’s Family Law Doctrine Revisited, 456-62. Consider the Court’s opinions on the paternity rights of unmarried fathers. For instance, the biological father in Stanley v. Illinois maintained custody of his children, despite not being married to their mother, because they all lived together like a nuclear family for many years before the mother’s death. 405 U.S. 645, 651 (1972). In contrast, the biological father in Lehr v. Robertson did not maintain parental rights of his child because he was neither married to the mother nor involved in the child’s life—his relationship with his child and the child’s mother did not mimic a nuclear family. 463 U.S. 248, 266-67 (1982). Finally, the biological father in Michael H. v. Gerald D. did not maintain visitation with his child because the mother was married to someone else; the Court found preserving the nuclear family emanating from the marital relationship more important than preserving a father-daughter relationship forged outside of that setting. 491 U.S. 110, 120 (1989). These decisions say to me that the nuclear family structure is not just an underlying social force in our culture; it is actively recognized and protected as some sort of higher social good by our highest court. My question is: why? Why are nuclear families important to the exclusion of other family structures?

Despite our covert and overt prioritization of the nuclear structure, there are a lot of families out there that do not fit, or even resemble, that mold. I didn’t seriously consider the existence or viability of “alternative” family structures until my niece was born in 2001, when I started studying the federal Indian Child Welfare Act. That piece of legislation attempts to interject cultural relativism into state child welfare proceedings involving Indian children. That is, it attempts to force state courts in these proceedings to recognize that Indian families do not necessarily conform to the nuclear structure. In its congressional findings, the Act states “that the States, exercising their recognized jurisdiction over Indian child custody proceedings . . . have often failed to recognize the essential tribal relations of Indian people and the cultural and social standards prevailing in Indian communities and families.” 25 U.S.C. § 1901(5). For many Indian tribes, extended family members play a central role in raising Indian children, and parents commonly leave their children with such relatives for long periods of time. B.J. Jones, The Indian Child Welfare Act Handbook, 3 (1995). Because placing a child with extended relatives is a normal part of childrearing in many tribal cultures, the Act sought to eliminate a state’s ability to remove Indian children based on the dominant culture’s presumptions about who and what make up a family; in essence, the Act attempts to recognize and protect Indian families functioning in structures other than nuclear.

Now, keep in mind that Indian families receive very specific federal recognition and protection because tribes are semi-sovereign nations with the ability to self-govern. Yet, these are not the only families outside the traditional that warrant recognition and protection. Indeed, other “alternative” family structures are fighting for legitimacy as I write this. Consider the federal challenge to California’s Proposition 8, currently being litigated in the Northern District of California. The plaintiffs in this trial are fighting for the rights of same-sex couples to get married; to be legally recognized as families and to receive legal protections as such. Though a same-sex marriage is “alternative” in comparison to a heterosexual marriage, it still follows the pattern of a nuclear family (two adults who partake in a legal relationship and who have children pursuant to that relationship if they choose). At the end of the first week of trial, one of the attorneys challenging Proposition 8, Ted Olson, attempted to make the anti-Prop 8 case to conservatives by linking same-sex marriage to the traditional social norms a nuclear family structure promotes and protects. Olson, The Conservative Case for Gay Marriage. Further, judging from Olson’s Newsweek piece and the live courtroom tweets from @ilona and @NCLRights, many of the plaintiffs’ witnesses in this trial have focused on the similarities between long-term heterosexual relationships and long-term same-sex relationships; how these binary relationships promote the traditional values of a nuclear family, and accordingly, societal stability.

Here’s where I get back to The Girls Next Door. I reject the notion that the nuclear family paradigm is the end-all, be-all family structure, the only permutation of a family that can promote societal stability and social good. Federal law requires recognition and protection of non-nuclear Indian families, and legal recognition of same-sex marriage is really just recognition of a nontraditional form of the nuclear family. What about nontraditional, non-nuclear family structures for people outside of special-circumstance groups? I’ve come to the conclusion that if I’m going to respect and fight for some types of alternative family structures, I at least have to openly and honestly consider the value inherent in all types of alternative family structures. After all, just because you personally dislike the way a certain group of people lives, that doesn’t mean it’s objectively problematic and devoid of social value. And we live in the United States; people have constitutional rights regarding whom they associate with. Why shouldn’t different familial structures be recognized and protected in accordance with those rights?

I would submit that Hef and his girlfriends practice what seems to be a socially acceptable form of what our country understands as polygamy. The girls live in the same house, have intimate relationships with Hef, and share him with a seemingly minimal amount of jealousy. There is a head girlfriend, and she has a certain amount of authority over the others. Though there are no children, this is only because the head-of-household is not interested in siring any more. Considering all this, it seems strange that a wealthy octogenarian in Southern California can live in an open relationship with a group of young (sometimes barely eighteen), beautiful women, have the situation put on television, and no one bats an eye; at the same time, similarly-structured families in Utah, Arizona, and Texas have their children removed by child protective services basically for living the same way. See Fox News, Polygamist Parents Complain “Vague” Custody Plans Impossible to Follow (March 20, 2008). If these two groups are the same, then both deserve recognition and protection; both should be legitimized as families.

I realize this thought, that a polygamous family—be it on television in Hollywood or in hiding out on a compound in the Southwest—should have legal recognition and protection, raises concerns about oppression and abuse. Polygamy, in the tradition of the Church of Latter Day Saints, does subjugate women. But the practice of plural marriage itself does not necessarily do so. This is evidenced by the multiple terms utilized to describe different types of plural marriage: according to Wikipedia, “polygamy” is an umbrella term covering both “polygyny” (where a man has more than one wife) and “polyandry” (where a woman has more than one husband). Putting aside our history and gender roles, it is possible for a polygamous family to consist of one wife with multiple husbands. But even inside a polygamous marriage with one husband and multiple wives, the relationship does not have to be one of subjugation, or, at least not any more than any other heterosexual marriage.

Further, regarding underage sex crimes and domestic violence, protections against such behavior within a traditional marriage exist. State laws are beginning to permeate the black box of heterosexual marriage, and presumably these laws can also be used to address problems within a plural marriage. I understand state authorities have difficulty prosecuting sex abuse, child abuse, and domestic violence within polygamous LDS sects, regardless of the laws on the books. This seems to be because these sects have completely closed themselves off from modern society to avoid persecution, and consequently are virtually inaccessible to the outside world, including law enforcement. But if polygamy were legally sanctioned as an acceptable form of family, those doors would probably open up, and state protections against criminal behavior in polygamous relationships could become more effective.

We legitimize Hef and The Girls Next Door by putting them on television. Let’s call them what they are: a family. If we at least socially recognize Hef’s “alternative” family, we need to afford the same recognition to other permutations of this structure. We have criminal codes to take care of the sex abuse and domestic violence alleged in these situations. But as far as I can tell, there is nothing in the constitution prohibiting us from recognizing polygamous family structures along with the other alternative structures we already recognize and protect (or are fighting to recognize and protect).

I know there is some concern about how to draw the line: who counts as family, and who is just trying to scam the system for personal gain? I don’t know how to draw that line; I don’t know which associations “deserve” to be considered family and which do not. Do we really need a line at all? Don’t the personal benefits that any familial relationship brings an individual help that individual contribute positively to our society? Who cares whether my family is mine by blood, legal ties, or my choosing? In actuality, I have all three, and my chosen family is just as pivotal in my life as the biologicals or the legals. I love them with my entire heart; we have followed each other all over the country, we have lived together, we have celebrated birthdays, holidays, and milestones together, we have met each other’s biological families, we have fought, we have made up . . . we consider ourselves as close as any traditional family. My association with them helped me accomplish things I could have never done on my own: finish a thesis, graduate from college, attend law school. They make me a better person, and as a better person, I have more to give back to the world. If a family structure offers an individual these benefits, I don’t see how that structure could not benefit our society; any structure that brings those benefits deserves to be recognized, protected, and promoted.